Simulating product failures

I’m inspired by this post here (http://www.programmingr.com/examples/neat-tricks/sample-r-function/rexp/). And decided to expand on the example.

Say you are an owner of a computer store and you would like to estimate the frequency of warranty repairs - and the ensuing costs.

Here’s the scenario with the accompanying assumptions

- Each computer is expected to last an average of 7 years

- You only sell 1000 computers at the start of each year

- You sell computer from 2019 to 2025

First, I simulate an exponential distribution of 1000 points for 7 years; and place a time index of 2019 to 2025

set.seed(1)

library(tidyr)

sim_repair_time = mapply(rexp, rep(1000, 7), rep(1/7, 7))

sim_repair_time = data.frame(sim_repair_time)

names(sim_repair_time) = paste0("Y", 2019:2025)

sim_repair_time$comp_index = 1:nrow(sim_repair_time)

head(sim_repair_time)## Y2019 Y2020 Y2021 Y2022 Y2023 Y2024 Y2025

## 1 5.2862728 7.0456022 4.4584814 2.987471 2.4983623 1.155475 3.526856

## 2 8.2714995 0.3831851 21.3583423 16.976357 0.6371918 19.870135 8.339298

## 3 1.0199471 6.1577002 24.7270286 7.184722 13.6686444 2.692336 1.531733

## 4 0.9785668 2.0554758 4.0556961 11.680879 3.4047724 8.547126 4.098845

## 5 3.0524804 1.3899782 0.8014122 7.394160 10.8930823 1.088804 8.679067

## 6 20.2647798 1.1392965 8.5595344 3.423599 5.0281127 8.178582 15.854250

## comp_index

## 1 1

## 2 2

## 3 3

## 4 4

## 5 5

## 6 6Then, I - in dplyr lingo - gather the dataset (convert to long form)

sim_repair_time = sim_repair_time %>% gather(key = year,

value = spoilt_years_later,

-comp_index)

sim_repair_time$year = gsub("Y", "", sim_repair_time$year)

head(sim_repair_time, 50)## comp_index year spoilt_years_later

## 1 1 2019 5.2862728

## 2 2 2019 8.2714995

## 3 3 2019 1.0199471

## 4 4 2019 0.9785668

## 5 5 2019 3.0524804

## 6 6 2019 20.2647798

## 7 7 2019 8.6069344

## 8 8 2019 3.7777799

## 9 9 2019 6.6959725

## 10 10 2019 1.0293219

## 11 11 2019 9.7351459

## 12 12 2019 5.3342090

## 13 13 2019 8.6632249

## 14 14 2019 30.9675395

## 15 15 2019 7.3818022

## 16 16 2019 7.2467076

## 17 17 2019 13.1322462

## 18 18 2019 4.5832265

## 19 19 2019 2.3585343

## 20 20 2019 4.1193581

## 21 21 2019 16.5516068

## 22 22 2019 4.4932481

## 23 23 2019 2.0588427

## 24 24 2019 3.9610587

## 25 25 2019 0.7425084

## 26 26 2019 0.4160741

## 27 27 2019 4.0509872

## 28 28 2019 27.7125300

## 29 29 2019 8.2131847

## 30 30 2019 6.9776907

## 31 31 2019 10.0469974

## 32 32 2019 0.2608797

## 33 33 2019 2.2680711

## 34 34 2019 9.2432755

## 35 35 2019 1.4245725

## 36 36 2019 7.1590811

## 37 37 2019 2.1121865

## 38 38 2019 5.0765001

## 39 39 2019 5.2607988

## 40 40 2019 1.6451922

## 41 41 2019 7.5591680

## 42 42 2019 7.1977283

## 43 43 2019 9.0458315

## 44 44 2019 8.7717375

## 45 45 2019 3.8824898

## 46 46 2019 2.1089810

## 47 47 2019 9.0518726

## 48 48 2019 6.9618905

## 49 49 2019 3.5992201

## 50 50 2019 14.0548268Lastly, I add the time taken for each computer to break down to the year for which the computer is bought.

#sim_repair_time$spoilt_years_later = round(sim_repair_time$spoilt_years_later, 0)

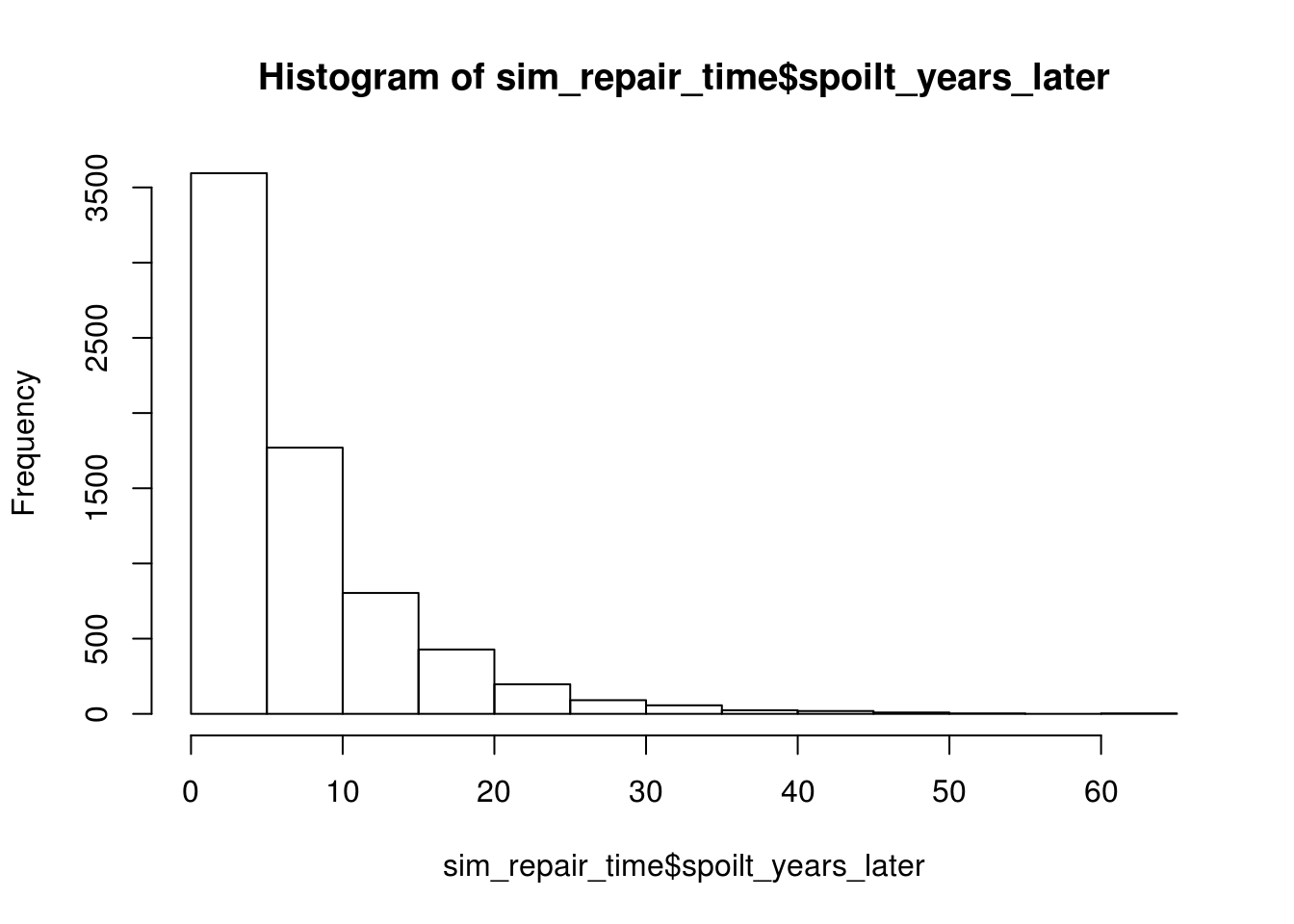

sim_repair_time$year_spoilt = sim_repair_time$spoilt_years_later + as.numeric(sim_repair_time$year)Here is the distribution of years taken that a computer will break down.

hist(sim_repair_time$spoilt_years_later)

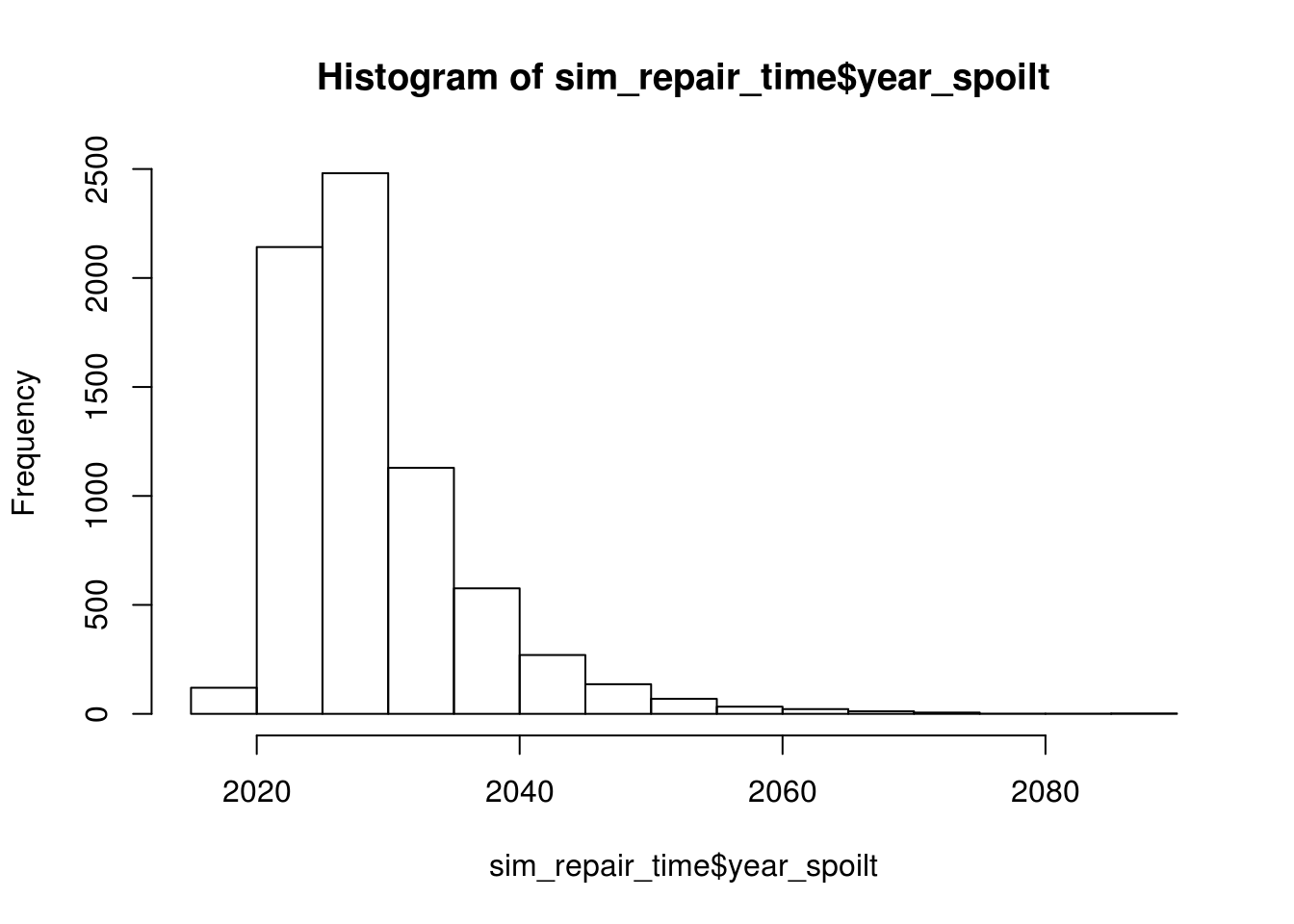

And here is the distribution of the years that the computer will break down.

hist(sim_repair_time$year_spoilt)

Explaining exponential distribution from first principle

If you are keen from the first principle perspective,

\[f(x) = {\lambda}e^{-\lambda x} \]

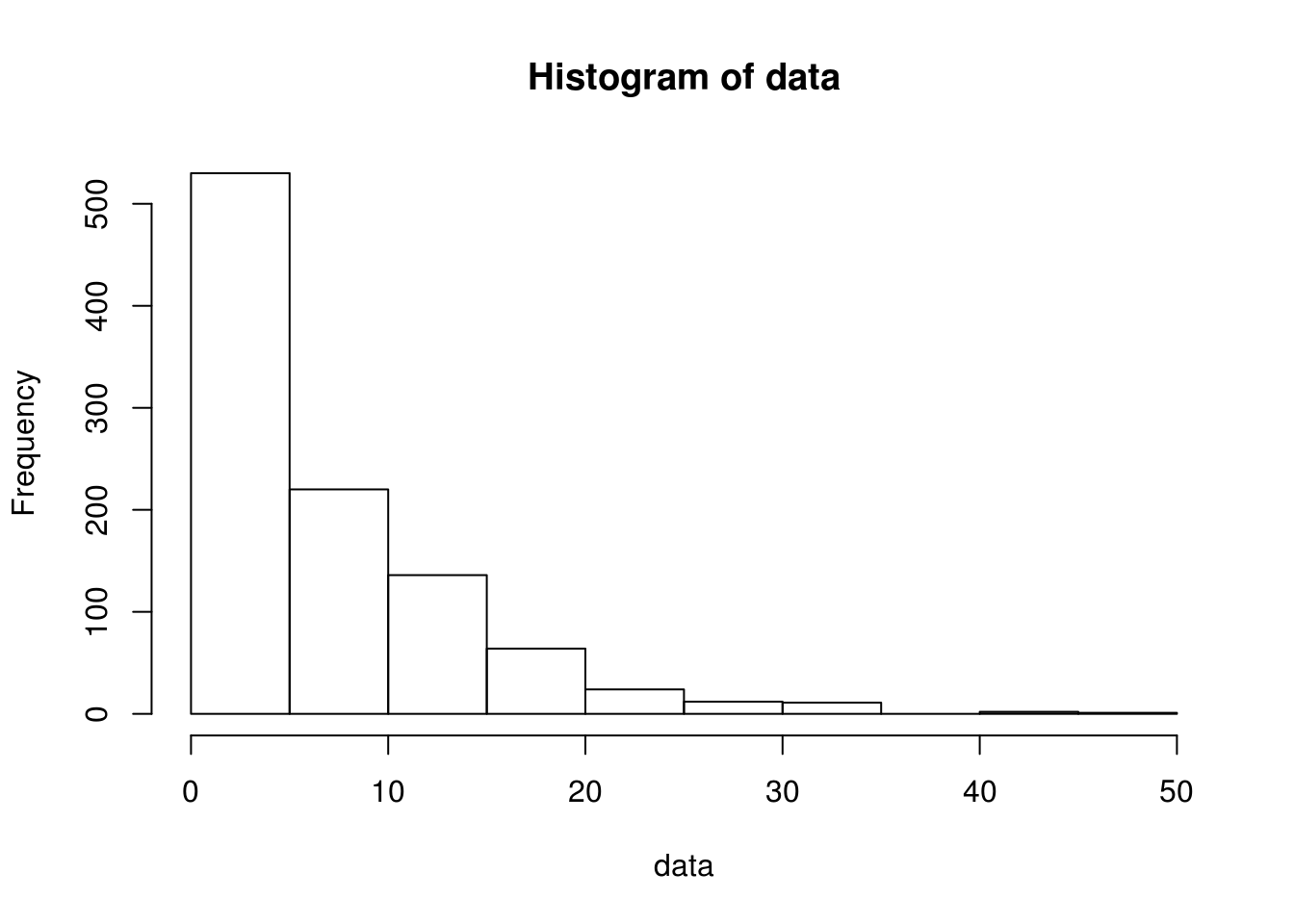

To understand pdf function here. It’s pretty simple. If you run the simulator 1000 times with mean = 7 (lambda = 1/7), and you plot the distribution, it’s mostly likely to be front-loaded.

If you fit a series of values x - N to the above function, it will be pretty similar to simulated series of values.

And if you do a mean of the simulated data, it will return close to the mean of 7

data = rexp(1000, 1/7)

hist(data)

mean(data)## [1] 6.775649I hope this simple example here is useful!